Four color theorem

In mathematics, the four color theorem, or the four color map theorem states that, given any separation of a plane into contiguous regions, producing a figure called a map, no more than four colors are required to color the regions of the map so that no two adjacent regions have the same color. Two regions are called adjacent if they share a common boundary that is not a corner, where corners are the points shared by three or more regions.[1] For example, Utah and Arizona are adjacent, but Utah and New Mexico, which only share a point that also belongs to Arizona and Colorado, are not.

Despite the motivation from coloring political maps of countries, the theorem is not of particular interest to mapmakers. According to an article by the math historian Kenneth May (Wilson 2002, 2), "Maps utilizing only four colours are rare, and those that do usually require only three. Books on cartography and the history of mapmaking do not mention the four-color property."

Three colors are adequate for simpler maps, but an additional fourth color is required for some maps, such as a map in which one region is surrounded by an odd number of other regions that touch each other in a cycle. The five color theorem, which has a short elementary proof, states that five colors suffice to color a map and was proven in the late 19th century (Heawood 1890); however, proving that four colors suffice turned out to be significantly harder. A number of false proofs and false counterexamples have appeared since the first statement of the four color theorem in 1852.

The four color theorem was proven in 1976 by Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken. It was the first major theorem to be proved using a computer. Appel and Haken's approach started by showing that there is a particular set of 1,936 maps, each of which cannot be part of a smallest-sized counterexample to the four color theorem. Appel and Haken used a special-purpose computer program to confirm that each of these maps had this property. Additionally, any map (regardless of whether it is a counterexample or not) must have a portion that looks like one of these 1,936 maps. Showing this required hundreds of pages of hand analysis. Appel and Haken concluded that no smallest counterexamples existed because any must contain, yet not contain, one of these 1,936 maps. This contradiction means there are no counterexamples at all and that the theorem is therefore true. Initially, their proof was not accepted by all mathematicians because the computer-assisted proof was infeasible for a human to check by hand (Swart 1980). Since then the proof has gained wider acceptance, although doubts remain (Wilson 2002, 216–222).

To dispel remaining doubt about the Appel–Haken proof, a simpler proof using the same ideas and still relying on computers was published in 1997 by Robertson, Sanders, Seymour, and Thomas. Additionally in 2005, the theorem was proven by Georges Gonthier with general purpose theorem proving software.

Contents |

Precise formulation of the theorem

The intuitive statement of the four color theorem, i.e. 'that given any separation of a plane into contiguous regions, called a map, the regions can be colored using at most four colors so that no two adjacent regions have the same color', needs to be interpreted appropriately to be correct. For example, each region of the map should be contiguous.

In the real world, not all countries are contiguous (e.g., Alaska as part of the United States, Nakhchivan as part of Azerbaijan, and Kaliningrad as part of Russia are not contiguous). Because the territory of a particular country must be the same color, four colors may not be sufficient. For instance, consider a simplified map:

In this map, the two regions labeled A belong to the same country, and must be the same color. This map then requires five colors, since the two A regions together are contiguous with four other regions, each of which is contiguous with all the others. If A consisted of three regions, six or more colors might be required; one can construct maps that require an arbitrarily high number of colors.

An easier to state version of the theorem uses graph theory. The set of regions of a map can be represented more abstractly as an undirected graph that has a vertex for each region and an edge for every pair of regions that share a boundary segment. This graph is planar: it can be drawn in the plane without crossings by placing each vertex at an arbitrarily chosen location within the region to which it corresponds, and by drawing the edges as curves that lead without crossing within each region from the vertex location to each shared boundary point of the region. Conversely any planar graph can be formed from a map in this way. In graph-theoretic terminology, the four-color theorem states that the vertices of every planar graph can be colored with at most four colors so that no two adjacent vertices receive the same color, or for short, "every planar graph is four-colorable" (Thomas 1998, p. 849; Wilson 2002).

History

Early proof attempts

The conjecture was first proposed in 1852 when Francis Guthrie, while trying to color the map of counties of England, noticed that only four different colors were needed. At the time, Guthrie's brother, Fredrick, was a student of Augustus De Morgan at University College. Francis inquired with Fredrick regarding it, who then took it to De Morgan (Francis Guthrie graduated later in 1852, and later became a professor of mathematics in South Africa). According to De Morgan:

"A student of mine [Guthrie] asked me to day to give him a reason for a fact which I did not know was a fact — and do not yet. He says that if a figure be any how divided and the compartments differently coloured so that figures with any portion of common boundary line are differently coloured — four colours may be wanted but not more — the following is his case in which four colours are wanted. Query cannot a necessity for five or more be invented… "(Wilson 2002, p. 18)

The first published reference is by Arthur Cayley who in turn credits the conjecture to De Morgan (Cayley 1879).

There were several early failed attempts at proving the theorem. One proof was given by Alfred Kempe in 1879, which was widely acclaimed; another was given by Peter Guthrie Tait in 1880. It was not until 1890 that Kempe's proof was shown incorrect by Percy Heawood, and 1891 Tait's proof was shown incorrect by Julius Petersen—each false proof stood unchallenged for 11 years (Thomas 1998, p. 848).

In 1890, in addition to exposing the flaw in Kempe's proof, Heawood proved the five color theorem (Heawood 1890) and generalized the four color conjecture to surfaces of arbitrary genus--see below.

Significant results were produced by Croatian mathematician Danilo Blanuša, who discovered two snarks in the 1940s, now known as Blanuša snarks; prior to Blanuša's discovery, the only known snark was the Petersen graph (Weisstein).

In 1943, Hugo Hadwiger formulated the Hadwiger conjecture (Hadwiger 1943), a far-reaching generalization of the four-color problem that still remains unsolved.

Proof by computer

During the 1960s and 1970s German mathematician Heinrich Heesch developed methods of using computers to search for a proof. Notably he was the first to use discharging for proving the theorem, which turned out to be important in the unavoidability portion of the subsequent Appel-Haken proof. He also expanded on the concept of reducibility and, along with Ken Durre, developed a computer test for it. Unfortunately, at this critical juncture, he was unable to procure the necessary supercomputer time to continue his work (Wilson 2002).

Others took up his methods and his computer-assisted approach. In 1976, while other teams of mathematicians were racing to complete proofs, Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken at the University of Illinois announced that they had proven the theorem. They were assisted in some algorithmic work by John A. Koch (Wilson 2002).

If the four-color conjecture were false, there would be at least one map with the smallest possible number of regions that requires five colors. The proof showed that such a minimal counterexample cannot exist, through the use of two technical concepts (Wilson 2002; Appel & Haken 1989; Thomas 1998, pp. 852–853):

- An unavoidable set contains regions such that every map must have at least one region from this collection.

- A reducible configuration is an arrangement of countries that cannot occur in a minimal counterexample. If a map contains a reducible configuration, then the map can be reduced to a smaller map. This smaller map has the condition that if it can be colored with four colors, then the original map can also. This implies that if the original map can not be colored with four colors the smaller map can't either and so the original map is not minimal.

Using mathematical rules and procedures based on properties of reducible configurations, Appel and Haken found an unavoidable set of reducible configurations, thus proving that a minimal counterexample to the four-color conjecture could not exist. Their proof reduced the infinitude of possible maps to 1,936 reducible configurations (later reduced to 1,476) which had to be checked one by one by computer and took over a thousand hours. This reducibility part of the work was independently double checked with different programs and computers. However, the unavoidability part of the proof was verified in over 400 pages of microfiche, which had to be checked by hand (Appel & Haken 1989).

Appel and Haken's announcement was widely reported by the news media around the world, and the math department at the University of Illinois used a postmark stating "Four colors suffice." At the same time the unusual nature of the proof—it was the first major theorem to be proven with extensive computer assistance—and the complexity of the human verifiable portion, aroused considerable controversy (Wilson 2002).

In the early 1980s, rumors spread of a flaw in the Appel-Haken proof. Ulrich Schmidt at RWTH Aachen examined Appel and Haken's proof for his master's thesis (Wilson 2002, 225). He had checked about 40% of the unavoidability portion and found a significant error in the discharging procedure (Appel & Haken 1989). In 1986, Appel and Haken were asked by the editor of Mathematical Intelligencer to write an article addressing the rumors of flaws in their proof. They responded that the rumors were due to a "misinterpretation of [Schmidt's] results" and obliged with a detailed article (Wilson 2002, 225–226). Their magnum opus, a book claiming a complete and detailed proof (with a microfiche supplement of over 400 pages), appeared in 1989 and explained Schmidt's discovery and several further errors found by others (Appel & Haken 1989).

Simplification and verification

Since the proving of the theorem, efficient algorithms have been found for 4-coloring maps requiring only O(n2) time, where n is the number of vertices. In 1996, Neil Robertson, Daniel P. Sanders, Paul Seymour, and Robin Thomas created a quadratic time algorithm, improving on a quartic algorithm based on Appel and Haken’s proof (Thomas 1995; Robertson et al. 1996). This new proof is similar to Appel and Haken's but more efficient because it reduced the complexity of the problem and required checking only 633 reducible configurations. Both the unavoidability and reducibility parts of this new proof must be executed by computer and are impractical to check by hand (Thomas 1998, pp. 852–853). In 2001 the same authors announced an alternative proof, by proving the snark theorem (Thomas; Pegg et al. 2002).

In 2005 Benjamin Werner and Georges Gonthier formalized a proof of the theorem inside the Coq proof assistant. This removed the need to trust the various computer programs used to verify particular cases; it is only necessary to trust the Coq kernel (Gonthier 2008).

Summary of proof ideas

The following discussion is a summary based on the introduction to Appel and Haken's book Every Planar Map is Four Colorable (Appel & Haken 1989). Although flawed, Kempe's original purported proof of the four color theorem provided some of the basic tools later used to prove it. The explanation here is reworded in terms of the modern graph theory formulation above.

Kempe's argument goes as follows. First, if planar regions separated by the graph are not triangulated, i.e. do not have exactly three edges in their boundaries, we can add edges without introducing new vertices in order to make every region triangular, including the unbounded outer region. If this triangulated graph is colorable using four colors or less, so is the original graph since the same coloring is valid if edges are removed. So it suffices to prove the four color theorem for triangulated graphs to prove it for all planar graphs, and without loss of generality we assume the graph is triangulated.

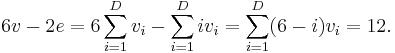

Suppose v, e, and f are the number of vertices, edges, and regions. Since each region is triangular and each edge is shared by two regions, we have that 2e = 3f. This together with Euler's formula v − e + f = 2 can be used to show that 6v − 2e = 12. Now, the degree of a vertex is the number of edges abutting it. If vn is the number of vertices of degree n and D is the maximum degree of any vertex,

But since 12 > 0 and 6 − i ≤ 0 for all i ≥ 6, this demonstrates that there is at least one vertex of degree 5 or less.

If there is a graph requiring 5 colors, then there is a minimal such graph, where removing any vertex makes it four-colorable. Call this graph G. G cannot have a vertex of degree 3 or less, because if d(v) ≤ 3, we can remove v from G, four-color the smaller graph, then add back v and extend the four-coloring to it by choosing a color different from its neighbors.

Kempe also showed correctly that G can have no vertex of degree 4. As before we remove the vertex v and four-color the remaining vertices. If all four neighbors of v are different colors, say red, green, blue, and yellow in clockwise order, we look for an alternating path of vertices colored red and blue joining the red and blue neighbors. Such a path is called a Kempe chain. There may be a Kempe chain joining the red and blue neighbors, and there may be a Kempe chain joining the green and yellow neighbors, but not both, since these two paths would necessarily intersect, and the vertex where they intersect cannot be colored. Suppose it is the red and blue neighbors that are not chained together. Explore all vertices attached to the red neighbor by red-blue alternating paths, and then reverse the colors red and blue on all these vertices. The result is still a valid four-coloring, and v can now be added back and colored red.

This leaves only the case where G has a vertex of degree 5; but Kempe's argument was flawed for this case. Heawood noticed Kempe's mistake and also observed that if one was satisfied with proving only five colors are needed, one could run through the above argument (changing only that the minimal counterexample requires 6 colors) and use Kempe chains in the degree 5 situation to prove the five color theorem.

In any case, to deal with this degree 5 vertex case requires a more complicated notion than removing a vertex. Rather the form of the argument is generalized to considering configurations, which are connected subgraphs of G with the degree of each vertex (in G) specified. For example, the case described in degree 4 vertex situation is the configuration consisting of a single vertex labelled as having degree 4 in G. As above, it suffices to demonstrate that if the configuration is removed and the remaining graph four-colored, then the coloring can be modified in such a way that when the configuration is re-added, the four-coloring can be extended to it as well. A configuration for which this is possible is called a reducible configuration. If at least one of a set of configurations must occur somewhere in G, that set is called unavoidable. The argument above began by giving an unavoidable set of five configurations (a single vertex with degree 1, a single vertex with degree 2, ..., a single vertex with degree 5) and then proceeded to show that the first 4 are reducible; to exhibit an unavoidable set of configurations where every configuration in the set is reducible would prove the theorem.

Because G is triangular, the degree of each vertex in a configuration is known, and all edges internal to the configuration are known, the number of vertices in G adjacent to a given configuration is fixed, and they are joined in a cycle. These vertices form the ring of the configuration; a configuration with k vertices in its ring is a k-ring configuration, and the configuration together with its ring is called the ringed configuration. As in the simple cases above, one may enumerate all distinct four-colorings of the ring; any coloring that can be extended without modification to a coloring of the configuration is called initially good. For example, the single-vertex configuration above with 3 or less neighbors were initially good. In general, the surrounding graph must be systematically recolored to turn the ring's coloring into a good one, as was done in the case above where there were 4 neighbors; for a general configuration with a larger ring, this requires more complex techniques. Because of the large number of distinct four-colorings of the ring, this is the primary step requiring computer assistance.

Finally, it remains to identify an unavoidable set of configurations amenable to reduction by this procedure. The primary method used to discover such a set is the method of discharging. The intuitive idea underlying discharging is to consider the planar graph as an electrical network. Initially positive and negative "electrical charge" is distributed amongst the vertices so that the total is positive.

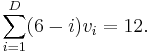

Recall the formula above:

Each vertex is assigned an initial charge of 6-deg(v). Then one "flows" the charge by systematically redistributing the charge from a vertex to its neighboring vertices according to a set of rules, the discharging procedure. Since charge is preserved, some vertices still have positive charge. The rules restrict the possibilities for configurations of positively-charged vertices, so enumerating all such possible configurations gives an unavoidable set.

As long as some member of the unavoidable set is not reducible, the discharging procedure is modified to eliminate it (while introducing other configurations). Appel and Haken's final discharging procedure was extremely complex and, together with a description of the resulting unavoidable configuration set, filled a 400-page volume, but the configurations it generated could be checked mechanically to be reducible. Verifying the volume describing the unavoidable configuration set itself was done by peer review over a period of several years.

A technical detail not discussed here but required to complete the proof is immersion reducibility.

False disproofs

The four color theorem has been notorious for attracting a large number of false proofs and disproofs in its long history. At first, The New York Times refused as a matter of policy to report on the Appel–Haken proof, fearing that the proof would be shown false like the ones before it (Wilson 2002). Some alleged proofs, like Kempe's and Tait's mentioned above, stood under public scrutiny for over a decade before they were exposed. But many more, authored by amateurs, were never published at all.

Generally, the simplest, though invalid, counterexamples attempt to create one region which touches all other regions. This forces the remaining regions to be colored with only three colors. Because the four color theorem is true, this is always possible; however, because the person drawing the map is focused on the one large region, he fails to notice that the remaining regions can in fact be colored with three colors.

This trick can be generalized: there are many maps where if the colors of some regions are selected beforehand, it becomes impossible to color the remaining regions without exceeding four colors. A casual verifier of the counterexample may not think to change the colors of these regions, so that the counterexample will appear as though it is valid.

Perhaps one effect underlying this common misconception is the fact that the color restriction is not transitive: a region only has to be colored differently from regions it touches directly, not regions touching regions that it touches. If this were the restriction, planar graphs would require arbitrarily large numbers of colors.

Other false disproofs violate the assumptions of the theorem in unexpected ways, such as using a region that consists of multiple disconnected parts, or disallowing regions of the same color from touching at a point.

Generalizations

The four-color theorem applies not only to finite planar graphs, but also to infinite graphs that can be drawn without crossings in the plane, and even more generally to infinite graphs (possibly with an uncountable number of vertices) for which every finite subgraph is planar. To prove this, one can combine a proof of the theorem for finite planar graphs with the De Bruijn–Erdős theorem stating that, if every finite subgraph of an infinite graph is k-colorable, then the whole graph is also k-colorable Nash-Williams (1967).

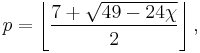

One can also consider the coloring problem on surfaces other than the plane (Weisstein). The problem on the sphere or cylinder is equivalent to that on the plane. For closed (orientable or non-orientable) surfaces with positive genus, the maximum number p of colors needed depends on the surface's Euler characteristic χ according to the formula

where the outermost brackets denote the floor function.

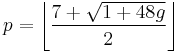

Alternatively, for an orientable surface the formula can be given in terms of the genus of a surface, g:

-

(Weisstein).

(Weisstein).

This formula, the Heawood conjecture, was conjectured by P.J. Heawood in 1890 and proven by Gerhard Ringel and J. T. W. Youngs in 1968. The only exception to the formula is the Klein bottle, which has Euler characteristic 0 (hence the formula gives p = 7) and requires 6 colors, as shown by P. Franklin in 1934 (Weisstein).

For example, the torus has Euler characteristic χ = 0 (and genus g = 1) and thus p = 7, so no more than 7 colors are required to color any map on a torus. The Szilassi polyhedron is an example that requires seven colors.

A Möbius strip also requires six colors (Weisstein).

There is no obvious extension of the coloring result to three-dimensional solid regions. By using a set of n flexible rods, one can arrange that every rod touches every other rod. The set would then require n colors, or n+1 if you consider the empty space that also touches every rod. The number n can be taken to be any integer, as large as desired. Such examples were known to Fredrick Gurthrie in 1880 (Wilson 2002). Even for axis-parallel cuboids (considered to be adjacent when two cuboids share a two-dimensional boundary area) an unbounded number of colors may be necessary (Reed & Allwright 2008; Magnant & Martin (2011)).

See also

- Graph coloring

- the problem of finding optimal colorings of graphs that are not necessarily planar.

- Grötzsch's theorem

- triangle-free planar graphs are 3-colorable.

- Hadwiger–Nelson problem

- how many colors are needed to color the plane so that no two points at unit distance apart have the same color?

- List of sets of four countries that border one another

- Contemporary examples of national maps requiring four colors

- Apollonian network

- The planar graphs that require four colors and have exactly one four-coloring

Notes

- ^ Georges Gonthier (December, 2008). "Formal Proof---The Four-Color Theorem". Notices of the AMS 55 (11): 1382-1393.From this paper: Definitions: A planar map is a set of pairwise disjoint subsets of the plane, called regions. A simple map is one whose regions are connected open sets. Two regions of a map are adjacent if their respective closures have a common point that is not a corner of the map. A point is a corner of a map if and only if it belongs to the closures of at least three regions. Theorem: The regions of any simple planar map can be colored with only four colors, in such a way that any two adjacent regions have different colors.

References

- Allaire, F. (1997), "Another proof of the four colour theorem—Part I", Proceedings, 7th Manitoba Conference on Numerical Mathematics and Computing, Congr. Numer. 20: 3–72

- Appel, Kenneth; Haken, Wolfgang (1977), "Every Planar Map is Four Colorable Part I. Discharging", Illinois Journal of Mathematics 21: 429–490

- Appel, Kenneth; Haken, Wolfgang; Koch, John (1977), "Every Planar Map is Four Colorable Part II. Reducibility", Illinois Journal of Mathematics 21: 491–567

- Appel, Kenneth; Haken, Wolfgang (October 1977), "Solution of the Four Color Map Problem", Scientific American 237 (4): 108–121, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1077-108

- Appel, Kenneth; Haken, Wolfgang (1989), Every Planar Map is Four-Colorable, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-5103-9

- Bernhart, Frank R. (1977), "A digest of the four color theorem.", Journal of Graph Theory 1: 207–225, doi:10.1002/jgt.3190010305

- Cayley, Arthur (1879), "On the colourings of maps", Proc. Royal Geographical Society (Blackwell Publishing) 1 (4): 259–261, doi:10.2307/1799998, JSTOR 1799998

- Fritsch, Rudolf; Fritsch, Gerda (1998), The Four Color Theorem: History, Topological Foundations and Idea of Proof, New York: Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-98497-1

- Gonthier, Georges (2008), "Formal Proof—The Four-Color Theorem", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 55 (11): 1382–1393, http://www.ams.org/notices/200811/tx081101382p.pdf

- Gonthier, Georges (2005), A computer-checked proof of the four colour theorem, unpublished, http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/um/people/gonthier/4colproof.pdf

- Hadwiger, Hugo (1943), "Über eine Klassifikation der Streckenkomplexe", Vierteljschr. Naturforsch. Ges. Zürich 88: 133–143

- Heawood, P. J. (1890), "Map-Colour Theorem", Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, Oxford 24: 332–338

- Magnant, C.; Martin, D. M. (2011), "Coloring rectangular blocks in 3-space", Discussiones Mathematicae Graph Theory 31 (1): 161–170, http://www.discuss.wmie.uz.zgora.pl/php/discuss.php?ip=&url=plik&nIdA=21787&sTyp=HTML&nIdSesji=-1

- Nash-Williams, C. St. J. A. (1967), "Infinite graphs—a survey", J. Combinatorial Theory 3: 286–301, MR0214501.

- O'Connor; Robertson (1996), The Four Colour Theorem, MacTutor archive, http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/The_four_colour_theorem.html

- Pegg, A.; Melendez, J.; Berenguer, R.; Sendra, J. R.; Hernandez; Del Pino, J. (2002), "Book Review: The Colossal Book of Mathematics", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 49 (9): 1084–1086, Bibcode 2002ITED...49.1084A, doi:10.1109/TED.2002.1003756, http://www.ams.org/notices/200209/rev-pegg.pdf

- Reed, Bruce; Allwright, David (2008), "Painting the office", Mathematics-in-Industry Case Studies 1: 1–8, http://www.micsjournal.ca/index.php/mics/article/view/5

- Ringel, G.; Youngs, J.W.T. (1968), "Solution of the Heawood Map-Coloring Problem", Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 60 (2): 438–445, doi:10.1073/pnas.60.2.438, PMC 225066, PMID 16591648, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=225066

- Robertson, Neil; Sanders, Daniel P.; Seymour, Paul; Thomas, Robin (1996), "Efficiently four-coloring planar graphs", Efficiently four-coloring planar graphs, STOC'96: Proceedings of the twenty-eighth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, ACM Press, pp. 571–575, doi:10.1145/237814.238005

- Robertson, Neil; Sanders, Daniel P.; Seymour, Paul; Thomas, Robin (1997), "The Four-Colour Theorem", J. Combin. Theory Ser. B 70 (1): 2–44, doi:10.1006/jctb.1997.1750

- Saaty, Thomas; Kainen, Paul (1986), "The Four Color Problem: Assaults and Conquest", Science (New York: Dover Publications) 202 (4366): 424, Bibcode 1978Sci...202..424S, doi:10.1126/science.202.4366.424, ISBN 0-486-65092-8

- Swart, ER (1980), "The philosophical implications of the four-color problem", American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 87 (9): 697–702, doi:10.2307/2321855, JSTOR 2321855, http://mathdl.maa.org/images/upload_library/22/Ford/Swart697-707.pdf

- Thomas, Robin (1998), "An Update on the Four-Color Theorem", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 45 (7): 848–859, http://www.ams.org/notices/199807/thomas.pdf

- Thomas, Robin (1995), The Four Color Theorem, http://people.math.gatech.edu/~thomas/FC/fourcolor.html

- Thomas, Robin, Recent Excluded Minor Theorems for Graphs, p. 14, http://people.math.gatech.edu/~thomas/PAP/bcc.pdf

- Wilson, Robin (2002), Four Colors Suffice, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0-691-11533-8

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Blanuša snarks" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Map coloring" from MathWorld.